|

Soundclip:

|

| See

Steve's Hand-Written Lead Sheet |

|

Wes Montgomery's solo on: "Satin Doll"(Ellington) When noted producer/record executive, Orrin Keepnews wrote his liner notes for Wes Montgomery's debut LP, "WES MONTGOMERY TRIO: A DYNAMIC NEW SOUND"(Riverside) sometime late in 1959, he recounted the story of how "Cannonball" Adderley had recommended Wes to him in such glowing terms that, just 5 days after Cannon's insistence, Orrin was in Indianapolis to hear Montgomery for the first time.  During those years Wes was playing two gigs per night. The first, during regular bar/night club hours at the Turf Bar, and the second, after hours, at the Missile Room. At that time, Wes' regular trio-mates were organist Mel Rhyne and drummer Paul Parker. During his time on the roster at Riverside Records, Wes Montgomery would record with his organ trio three more times. This first recording contains only two Montgomery originals alongside standards by Jerome Kern; Lerner & Lane as well as Jazz standards by Thelonious Monk; Benny Golson; Horace Silver and here we are presenting to you Wes' solo on Duke Ellington's chestnut, "Satin Doll." During those years Wes was playing two gigs per night. The first, during regular bar/night club hours at the Turf Bar, and the second, after hours, at the Missile Room. At that time, Wes' regular trio-mates were organist Mel Rhyne and drummer Paul Parker. During his time on the roster at Riverside Records, Wes Montgomery would record with his organ trio three more times. This first recording contains only two Montgomery originals alongside standards by Jerome Kern; Lerner & Lane as well as Jazz standards by Thelonious Monk; Benny Golson; Horace Silver and here we are presenting to you Wes' solo on Duke Ellington's chestnut, "Satin Doll."Like most of the material Wes played and recorded with his organ trio, the arrangements all represented a great deal of care, detail, and the familiarity between the three musicians. Where melody and harmony are concerned, it is obvious that Wes and Mel Rhyne spent a goodly amount of time together crafting just how the organ would blend with Montgomery's chordal or linear interpretations of the standards. On "Satin Doll" the [A] sections are stated together by Rhyne's organ and Wes' block chords. Letter [B], while Wes continues on with the melody in chords, Rhyne pares down to only the walking bass line. On this particular tune, Rhyne solos first and Montgomery comps in a 4/4 Freddie Green-like style. Wes' solo consists of a full [A]-[A]-[B]-[A] chorus in single-note lines, which is then followed by a chord solo over the first three sections of the tune with Mel Rhyne only walking the bassline. For the last [A], they state it just as they did during the opening with a little [Tag] added for an ending, and a very Jazzy sounding last chord of B/C with an F# on top. Now let's take a look at Wes' one chorus of single-note lines. The first [A] section is characterized by Wes' arpeggios in triplet groupings and, what I might describe as, a "call and response" style of phrasing. By the latter I mean that a phrase in one bar is answered in a similar fashion in the following bar. If you look closely at the arpeggios in bars 1-3, they all place an emphasis on the 9th degree of the m7 chords. So, over the Dm7-G7, you find E-natural as an important note. And over the Em7-A7, F# is the note that he vaults to. School or not, formally trained or not, Wes certainly must have spent time grasping just how the basic triads function within chordal sounds, and how they create the 'extensions' about the basic chord tones. So, you will see F/D or F/G during bars 1-2 and then G/E or G/A for bars 3-4. In bar 5, over the Am7-D7, in 2nd-half of the bar you find a B-triad over the D7 which produces these tones: B(13th); F#(3rd); and D#/Eb(b9). As [A2] begins, we find Wes walking up what is the D Dorian mode from D-E-F and G and eventually C and D, an octave higher. Of course, what goes up, must come down. And the responding phrase in bars 11-12 do just that with the last note being his low-G, which is the lowest note played during the solo. In bars 13-14, over the non-resolving ii-Vs, Wes plays a series of ascending triplet arpeggios which again begin with a major triad built from the m3rd of each chord. That would be C-natural for Am7-D7, and Cb for Abm7-Db7. After the cadence to Cmaj7 in bar 15, Wes plays a wonderful transition to [B] by alluding to Abm7-Db7 with his line, even though Mel Rhyne does not play those chords there. It is like inserting the harmony of the chord, 1/2-step above where you are headed. So, as [B] will begin with Gm7, this makes perfect sense. And, above all, it sounds great!!!  The solo changes that Wes and Mel Rhyne came-up with for [B] show a great deal of harmonic creativity and the desire to put their own stamp of this Ellington classic, which had already been played and recorded on countless occasions. What makes these changes so terrific and a much greater challenge for soloing is the insertion of a b5 substitute ii-V. Just take a look at bar 2 as it leads into bar 3. And, as I pointed out before, the device of anticipating the coming chord by playing the related chord 1/2-step above. Examples of this can be found in bar 4 heading into 5, and bar 6 heading into bar 7. Whether or not Wes would have explained it in this manner, looking at the lines, it is clear that each of these minor areas was thought of in the related Dorian mode. The only chromaticism within this section appears in bar 4 over the Bbm7-Eb7. || Gm7 / C7 / | Dbm7(9) / Gb7(13) / | Fmaj7 / / / | Bbm7 / Eb7 / | | Am7 / D7 / | Ebm7 / Ab7(13) / | Dm7 / G7 / | Em7b5 / A7(alt.) / || For the final [A], Wes returns to the arpeggios in triplet groupings that he first revealed as the solo began. Again, the arpeggios vault to the 9th of the m7 chords in bars 1-4 of this section. Obviously, he found that note to be very expressive. It's a nice touch that, at the end of bar 4, he throws a b9(Bb) into the arpeggio as well. Often times, it is the perception of some that Jazz musicians don't practice the same forms of exercises that a Classical musician might have been exposed to, but this is, of course, completely false. Again, trained or not, Wes could hear the usefulness in studying the basic of line construction. Notice, in bar 7 of this section, how each of the notes in a basic C major triad(C-E-G) are preceded by its chromatic lower neighbor: B-C; F#-G; and D#-E. Where arpeggios are concerned, this is one of the most fundamental approaches one can learn. When everything has been assessed, and put in its proper place, Wes Montgomery's solo over Ellington's "Satin Doll" is really much more about improvising via arpeggios than the usual sense of endless running single-note lines. Although, if you just view the transcription, it can appear as though Wes never takes a single breath. There is not a half-note rest to be found, and the only quarter-note rests appear within the first 12 bars. That's not a lot! Yet, when listening, it never feels that way. Don't ask me to try and explain that! Please! The preoccupation with arpeggios reminds me of the wonderful [Tag] ending that Wes created and plays on his interpretation of "'Round Midnight" which, by no small coincidence, appears on this same recording, and even opens it. What significance would I attach to that? Only that it would be reasonable to assume that, the execution of arpeggios, during that time, was of a high enough interest for him that, they became a device which he mastered, and was able to leave behind after this recording. I don't literally mean "leave behind" - I just mean that sometimes one realizes that it is time to move on, to move forward. He was always moving forward in his way. But the very things which gave him such great success in the latter part of his career also limited his further growth. The insidious interference of record executives and producers placed Wes Montgomery, this great artist, in a commercial box when recording, and he was never able to really escape again. This is why the earlier recordings from the Riverside years, are so revered by his most ardent fans. I suppose that the "trade-off" for commercial success is that 10's of 10,000's of new fans were exposed to Wes' music. This can never be seen as a bad thing for a man who labored long and hard and had a large family. In many ways, "Satin Doll" might not seem to be the 'hippest' of tunes to be playing, at least not in the 21st Century. But, if one can find a fresh approach to such a tune, anything is possible. I suppose that, where the guitar is concerned, my other favorite version of this tune appears on "ORGAN GRINDER SWING" by Jimmy Smith, and features Kenny Burrell and Grady Tate. It has great swing and a wonderful sense of humor as well. However, you won't find any of the 'hipster' substitute changes that Wes Montgomery employed on the version that we've been discussing here. You might really enjoy this other version, and even doing a bit of a comparison test for yourself. Once again, from Khan's Korner 1, we are wishing everyone the best in 2009.

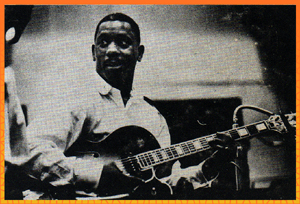

[Photo: Wes Montgomery and his Gibson L-5 in 1959

Photo by: Steve Schapiro] |